📚 On Graphic Novels in the Age of AI

I've been reading, and writing, comics lately. It's going surprisingly well!

I’ve been reading more graphic novels more lately, which should come as no surprise to anyone who read my article about why I don’t enjoy big, sprawling, multi-threaded epic narratives as much as some of my friends. The main surprise is that I didn’t have the epiphany that I should give comics another shot until after I wrote the article — which is fun from a “I write to articulate things to myself, first and foremost” perspective.

The secondary impetus behind this is that I noticed Jim Butcher finally finished writing the next Dresden Files installment, and I had a small stack of Dresden Files tie-in collections that I got for a holiday, but somehow forgot to read.

One of the things I noticed immediately is that the art is not very consistent, particularly in terms of the characters’ faces. It’s not a big deal, but the realization that even mainstream high-end graphic novels have the same problem I dislike most about AI-generated art was… enlightening.

It occurred to me, as I was having this slow-rolling revelation, that one of the biggest problems with using AI to write is the short context windows. And one of the advantages of writing scripts — as compared to prose — is that it’s a lot faster. There’s less text, more left to the imagination. A picture is worth a thousand words, and to be blunt, AI is much better at concept art than prose.

Novels are a very direct medium. They communicate with the end-user, a reader. When read aloud by a narrator, not that much is lost. The experience is what the author intends.

Scripts are different. A screenplay is necessarily a sketch; a team is intended to fill in the details. Directors add their own vision to the mix, actors develop the role, etc. But one of the interesting ways that comic scripts differ from screenplays is that there appears to be a much stronger relationship between writer and illustrator. With a screenplay, the writer makes a script and sells it. With mainstream television shows, there’s usually a huge team, and a large cast of actors.

Comics don’t have that, so there ends up being less standardization. The formatting expectations are much looser, and as a writer gets used to working with a particular artist, they get into a groove and the scripts don’t need to be as detailed. Or perhaps the writer will add something that really plays to a particular illustrator’s strengths.

I do not aspire to sell a comic script to Marvel, or Dark Horse, or Vertigo. But as long-time readers know, I do enjoy telling stories and developing fictional worlds. And for the last two weeks, I’ve been steadily chugging away at writing a comic book series with the help of the fountain plugin for Obsidian, which handles all the formatting for me. It’s interoperable with Beat, a fully open-source, incredibly elegant screenwriting app for macOS and iOS, created by a screenwriter who actually uses it for work… which solves what has historically been my biggest problem with writing fiction in Obsidian: export.

When I first started writing the script of The Dungeon Crawler’s Wife, I had it in my head that in a couple of years, maybe my kids could help me illustrate it1. Since my husband also enjoys graphic novels, I thought it might become be a fun family project, and provide some motivation for all of us to learn drafting and drawing skills.

Then OpenAI released their new image model — the one going viral because of the Studio Ghibli-style images. It is not perfect — it tends to repeat text, the layouts are not as dynamic as professional graphic novels, and it struggles to locate panels precisely where I want them — but it is genuinely much better at creating comic pages than I expected.

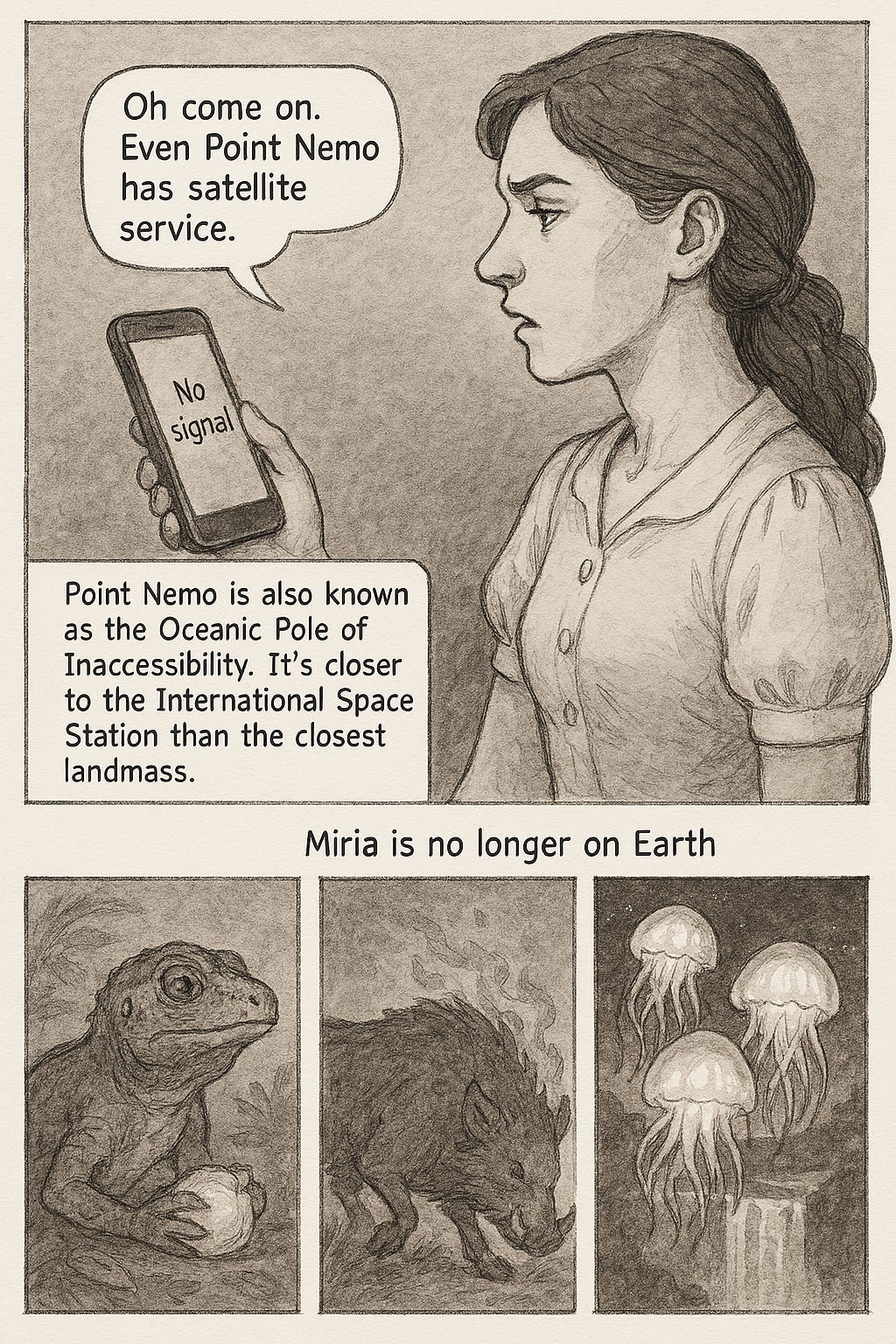

For the last two weeks, I’ve been writing at least a page of a comic script every evening. It’s been remarkably satisfying, not least of which because I’ve gotten back the spark of “oh! I can use that in my story!” when I read nonfiction books, or review old highlights. Framing things in the context has always helped me understand what I am reading. And now I get to insert fun facts about things like Point Nemo into my stories again. Like this:

## {{page}} no signal on phone

.PANEL {{panel}}: take up 3/4 of the page, with the bottom quarter forming a sort of “U” shape beneath it.

Miria stares at the “no signal” indicator on her phone.

MIRIA (SPEECH)

Oh come on. Even Point Nemo has satellite service.

CAPTION

Point Nemo is also known as the Oceanic Pole of Inaccessibility. It’s closer to the International Space Station than the closest landmass.

(cont)

Miria is no longer on Earth.

= - [ ] the phone is a Chekov's gun; make sure it comes in useful sometime, even if just to make a list or show photos of something.

.PANEL {{panel}}: BOTTOM LEFT position.

A colorful, pastel lizard chews a glowing orb of luminescent fruit while watching Miria warily.

.PANEL {{panel}}: BOTTOM CENTER position, a little shorter than the flanking panels.

A fiery boar paws at the ground, searching for grubs, or perhaps truffles.

.PANEL {{panel}}: BOTTOM RIGHT position.

A group of blue, bioluminescent jellyfish floats awkwardly above a waterfall that flows down into the abyss of THE VOID.

= - [ ] The jellyfish and boar will attack her in upcoming panels. I don’t currently have a plan for the lizard, but it should recur somehow later. It’s lightweight. I keep the whole thing in one file, and I don’t have to worry about numbering pages or panels. Sometimes, to help make sure what I have in mind works visually2, I use AI to sketch out the scene. I like to use a pencil sketch style so I don’t unconsciously make the mistake of thinking that the point is to create a finished product.

We’re at a weird point in the growth of AI technology. It continues to be strange to me that the computationally intensive thing we call AI is way better at making artistic images than, say, extracting all the URLs from a messy CSV file. I worry about becoming too reliant on it, probably in much the same way high school math teachers sometimes worried about calculators, or Socrates worried about books.

But I love books, and I love creating stories, and I’m grateful that I’ve found a way to get some forward momentum on projects I’ve had floating in my mind for years now… even if it means changing medium. Medium matters for storytelling — reading Hunger Games the book is an extremely different experience than watching the movie, and I highly recommend doing both and reflecting on the differences — but graphic novels have developed some really lovely associations in my family, and I’m looking forward to reading (and writing!) more.

Do y’all have any favorites I should check out?

One of the other interesting things about comic books is that they are not very satisfying to read out loud. A nice side effect of my newly rekindled love of comics is that it seems to have inspired my son to accelerate his literacy; almost every time he catches me reading a graphic novel, he ends up wanting to do a phonics lesson so he can learn to read faster.

I score a “5” on the Aphantasia scale, which is to say if you ask me to visualize an apple there is no picture of an apple in my mind.

Aphantasia at 5 for me as well unless I am in the process of waking up. Then my inner vision is so clear that I can read text.

Have you seen any Nodus Labs videos? The link is https://www.youtube.com/@noduslabs. The website is https://infranodus.com/. The blurb: Get a clear overview of any text, topic, or AI knowledge base. Uncover blind spots to generate actionable insights.